| I visited two rooftop gardens in Singapore in February 2024, along with other kitchen gardens in the “City in nature”. I also visited the National Institute of Education and explored the city-state’s long-standing environmental policies. |

I discovered Singapore during a twelve-day stay in January-February 2024. The city-state, a six-million inhabitants tropical island of Southeast Asia, is one of the most verdant metropolises on the planet. It didn’t happen by chance: Singapore has consistently worked to green itself since it was declared an independent republic in 1965.

This article, like its 30 June French version, explores recent collaborations between public authorities, real estate businesses and non-profit organisations aimed at greening the city further. We will look at two case studies: Funan Urban Farm and 1-Arden, two downtown rooftop kitchen gardens. I shall also report on my visit to the National Institute of Education, Singapore’s national teacher education institute.

After publishing my French article, I did further research into Singapore’s past and current environmental policies. It enabled me to add more context () and to show how much political vision can influence the transformation of a physical and social environment over the years. We start with this new chapter.

Singapore’s environmental policies

After a relatively unsuccessful tree-planting campaign launched in 1963, Singapore’s government unveiled their vision of a “Garden city” in 1967. The concept evolved, to be renamed “City in a garden” in 1998 and “City in nature” in 2020. I recommend design historian Jesse O’Neill’s 2023 article Singapore’s Garden city: the political language of urban planting. It demonstrated how much the city’s success in greening itself stemmed from a combination of political will, citizen engagement and debate in civil society. ‘The garden city became a framework for urban and social planning for more than five decades’, said O’Neill, a University of the Arts London colleague I’d like to meet. ‘Developing from the failed tree planting campaign of 1963, it was reintroduced to find popular success in the 1970s’. In his Abstract, he concluded: ‘Beyond creating a landscape of urban greenery, the garden shaped the long-term success of what began as an uncertain postcolonial nation’. I would add that during this period Singapore’s population tripled, the island reaching a density of 8,207 inhabitants per square kilometre in 2024, which makes the achievement all the more impressive.

The city’s environmental plans have been criticized all along, for instance by environmentalists at the end of the 1990s when the new ‘City in a garden’ concept was released. According to O’Neill, the policies were then seen by some as a ‘planned obliteration of nature in favour of the controlled simulacrum of the garden’. He referred to a 1998 article in the Straits Times, the most-widely circulated and trusted newspaper in the country, titled ‘Natural spaces are better than gardens’. In this short article, Dr Weinfei Tong, a biologist and environmental advocate who grew up in the urban landscape of Singapore, wrote: ‘the many manicured gardens smothered in concrete… have been subjected to excessive “beautification”… They lack the variety of indigenous flora and fauna which constitutes the vibrancy of a natural green space’. Environmentalists had already criticized the ‘Garden city’ policy in the 1980s. Referring to a 2014 article published in Nature Contained: Environmental Histories of Singapore called ‘A city in a garden’, O’Neill explained that ‘environmental groups such as the Nature Society began taking aim at the precarious notion of ‘nature’ that developed under this model. They made the point of how artificial the ‘garden’ had become, reflecting little of the original natural conditions of Southeast Asia.’

O’Neill observed that Singapore’s authorities learned from criticism and slowly evolved their concept. ‘Early arguments against the garden city by environmentalist movements had little initial effect in urban policy, but over time they began to shape understandings of the city and its connection with nature.’ The article Is Singapore a biophilic city? published by the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA), the city-state’s land use planning and conservation authority, is evidence of that. The concept of ‘biophilia’, which means ‘loving living things’ as explained in the article, has become instrumental to Singapore’s environmental policy. ‘Biophilic cities live in harmony with nature’. The city’s landscape has moved over the decades from what was perceived by critics as bare ornamental garden aesthetics to something now shaped by a more adequate, lovesome desire to live in nature.

“Biophilic” is the new motto: as we will see in the two case studies the term is now used by public authorities as well as private developers. In the URA article, the authorities affirmed that the aspiration had always been there. “We have actually been a biophilic city all this while”, said Dr Lena Chan, the senior director of the International Biodiversity Conservation Division, National Parks Board (NParks). “We always had the DNA in us to be green”, speaking from experience after decades of involvement in the city’s environmental policies.

Living in harmony with nature is an ambitious goal which brings new challenges, especially in such a densely populated and urbanised space. Cohabiting with wildlife is one of them. What to do when encountering a macaque, a snake, or even a wild boar, all present on the island? National Parks have published guidance aimed at citizens, but there are still risks. As for “wild” chickens, potentially less dangerous, they are not to everybody’s taste as they cause nuisance, the Straits Times reported in 2023. And what about the wellbeing of the animals? I was initially charmed by the beautiful feathers and the freedom of the roosters and hens I saw in Singapore’s streets. Thinking about it, how does their life on small green spaces and asphalt compare to that of the chickens which ran free in the large bare ground yard and the garden of my grandfather’s farm in rural France, or to the wild pheasants I often witness strolling in the lush British countryside? I guess I should be careful about my assumptions here: large green fields and forests are more familiar to me than the minerality of dense cities, and I shouldn’t infer that cities are not adequate habitats for wildlife. Monkeys for instance thrive in large cities. A more relevant question would be “Can humans and wildlife live in harmony with each other?”

To me, a “yes” answer to that question is the City in nature’s bet. It is a bold one, and one I support. I share Dr Chan’s view expressed at the end of her interview: ‘I hope our communities relearn to live and reconnect with nature because that is the best way for humankind to live sustainably’. Environmental policies are not just about the environment, they generate social harmony and societal progress. It was the modern Singapore founders’ vision sixty years ago, and still is.

Before we move to the chapters I published in French on 30 June, I would like to point to the kitchen gardening part of Singapore’s environmental policies. At the bottom of the five key strategies for a City in Nature by 2030 National Parks’ webpage, a ‘Community in bloom’ link takes us to a website section where citizens learn about Community Gardens, Allotment Gardens and Social Enterprise Community Urban Farms. They are encouraged to visit and join an existing edible garden or apply for funding to create a new one. It would take another article, and probably another trip to Singapore for me to write about these initiatives. I will stick to the places I actually visited in 2024. The two edible gardens below contribute to key strategy N°3 ‘Restore nature in urban areas’, which aims at having ‘200 hectares of skyrise greenery island-wide’ by 2030.

Two edible gardens on Singapore’s rooftops

On 10 and 11 February 2024, I visited two rooftop kitchen gardens in Downtown Core, the economic and cultural heart of Singapore. They were recommended to me by Edible Garden City, a social enterprise that promotes food self-provisioning and urban farms. I was unfortunately unable to meet their managers as they were on holiday during the week of the Chinese New Year.

Upon my return from Asia, I shared my experience with two of my MBA students at a networking event in London on 15 February 2024. E. had worked on a project to create a small mushroom production unit in the British capital, and J. is from Hong Kong, another dynamic Asian city. I sent them some information by email a few days later:

“Hello J. and E.,

So good to see you on Thursday! Here are the two rooftop gardens I visited in Singapore earlier this month. Edible Garden City, a social enterprise which contributed to their creation, advised me to go there as they are open to the public.

The “food forest” of 1-Arden:

Best wishes,

Jean-Jacques

150 edible plants, flowers, and fruit trees are grown on CapitaSpring’s rooftop garden. Perched 280 meters above the ground, 1-Arden is advertised as the ‘world’s highest urban food forest’. The best way to discover it is to watch this 10-minute video, shot ten months after the opening in 2022, which includes stunning bird’s eye views of the site. The head gardener takes us on a tour of the plants and their uses.

I also recommend the podcast (see above photo). It provides a better understanding of the ins and outs of this remarkable project, its limitations, and possible improvements. It discusses, for example, the quality of the soil. I was already told on site that the soil used was initially inert, coming from the excavation of the skyscraper’s foundations. It has been enriched, enabling for micro-organisms to develop and make the ecosystem more productive and less prone to diseases. It would have been wiser to use pre-prepared soil from the outset, provided, of course, that a suitable supplier could be found. The developers probably have already improved on this.

1-Arden and Funan Urban Farm are interesting examples of kitchen gardening innovation. They were also part of real estate projects which complied with Singapore’s urban planning regulations for the business and shopping district where they are located. The projects must ensure a minimum density of greenery on the construction or reconstruction site will be reached, measured by the Green Plot Ratio (to see the ratio’s formula, click on ‘Landscaping for Urban Spaces and High-Rises (LUSH)’ and then on ‘Landscape Replacement Areas (LRA) Guidelines in Strategic Areas’). The creative application of these rules by real estate firm CapitaLand and their design partners agency Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG) and Carlo Ratti Associati at CapitaSpring and Grant & Associates at Funan is evidence that businesses are key contributors to the virtuous circle that makes Singapore green, including in the most densely built-up areas, whether at the foot of buildings, on walls, on floors or on roofs. Public authorities, civil society and citizens couldn’t have created the ‘biophilic skyscraper CapitaSpring’ nor the Edible Garden City’s urban farm at Funan if the private sector had not taken the city-state’s green policies on board and experimented with practical implementations.

Here are some additional photos:

Learning through gardening

As we know, Singapore is renowned for the effectiveness of its education system. The country ranked first in 2022 in the three disciplines tracked by the OECD’s triennial PISA survey, which measures the skills of fifteen-year-old students in mathematics, science, and reading. Interested in education, my current career, I wanted to learn more.

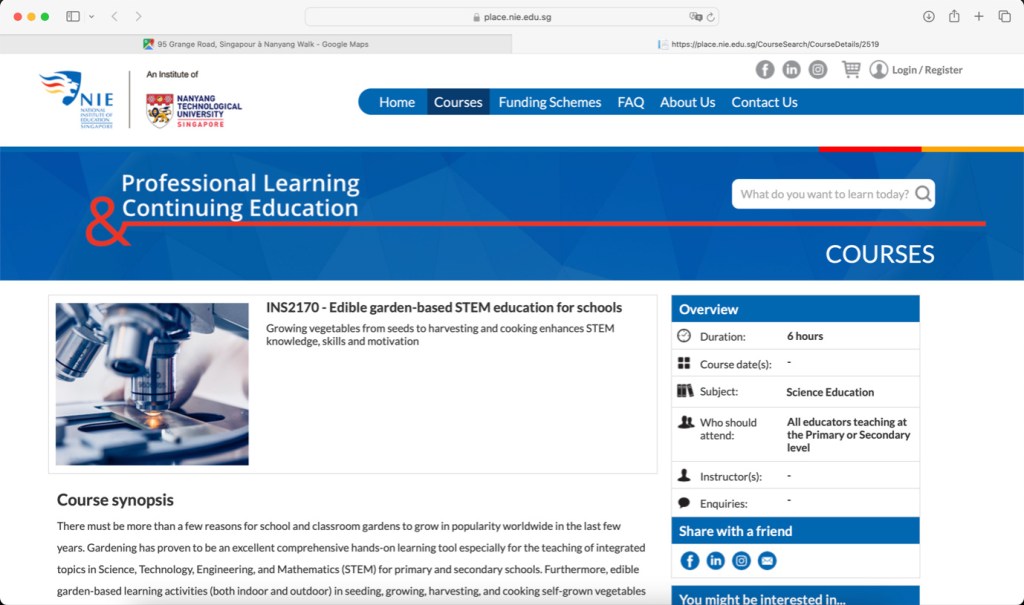

I visited the National Institute of Education (NIE), which trains the country’s teachers and contributes to research on teaching methods and practices. While preparing for my visit, I discovered this: a professional development module offered to primary and secondary school teachers that helps students learn about STEM disciplines (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) through gardening and cooking.

I went to the NIE Visitors Learning Centre on February 6 afternoon, where I spoke to one of the institute’s international relations officers. Unfortunately, I was unable to make an appointment with the creators of the gardening and cooking program before my return to Europe, as they too were on vacation for the Chinese New Year. I hope to have other opportunities to discuss how gardening and cooking practices can support education. I would enjoy sharing my own experience of it.

Other areas of interest

In relation to edible gardening, I would like to take a closer look at the public authorities’ planning regulations for green spaces in Singapore. This diagram drawn in the Landscaping for Urban Spaces and High-Rises (LUSH) plan is a point of entry for discovering the advanced urban policies of the city-state in areas of high urban density. Specific rules and guidance are available on the Urban Redevelopment Agency (URA) website, for instance for ‘communal planter boxes’ and ‘rooftop urban farming’. We could find inspiration for our own cities.

I also visited the Singapore City Gallery. This branch of URA enables visitors to discover how the metropolis has grown since the 1960s, which urban planning challenges it has faced and how they have been tackled. Their educational programs for students and teachers of all levels have been designed to ‘facilitate students’ understanding of how we plan for a liveable and sustainable Singapore’. The interactive learning experiences are a way of involving citizens, of encouraging them to actively contribute to the building of their city’s future.

From the initial vision of a ‘Garden city’ fostered by its founders in the 1960s to the current developments of its environmental, social, economic and educational policies, we have a lot to learn from Singapore.

Quelle métropole française pourrait se lancer ?

Hi Pierre, thanks for reading. Interesting question. I am not an urban development expert, however I see several possible strategies:

– Experiment in cities which are already advanced in greening themselves, such as Nantes. It would enable real estate projects to benefit from the landscape design and maintenance business ecosystem present there. I would say that Nantes Métropole is already like a small Singapore in temperate climate, with a lot more space available for urban development.

– Greater Paris would be an obvious choice as an affluent city with a buoyant property market. Paris intra-muros would be a great place to experiment given how highly mineral it is and how much greenery could make a difference in improving the beauty and the liveability of the capital.

– Cities most exposed to climate change?

That said, a genuine interest from local authorities in driving environmental policies aimed at enabling citizens to live in harmony with nature and each other is probably a prerequisite. To me, the main reason of Singapore’s success is in this genuine interest, continuously present since the 1960s.

I would also say that the opportunity is not limited to metropolises. Medium and even smaller cities might be in an even better position to create and benefit from a biophilic approach to urban development, in particular when located in more rural areas: they have a lot of space and could even more easily become “cities in nature”?

Pingback: News : Sustainability and care | Les Jardins d'ici