My kitchen garden was already cultivated two centuries ago. It was called “Le Jardin du Paradis”, the Garden of Paradise. Probably much older, it has been preserved by my family until 2022.

I discovered the name of my garden, “Le Jardin du Paradis”, during the autumn 2022. I was looking at my family’s archives, where I found official documents naming it thus. The oldest record dates back to 1794. The documents indicate that a large garden belonging to a farmer called Jean-Pierre Lintilhac was divided into several plots after the 1789 French Revolution. One of these plots was purchased by my ancestors in the middle of the 19th century. My family has carefully kept these archives which describe the origins of the place where I grew up and which I now own after the last member of the older generation passed away in 2021.

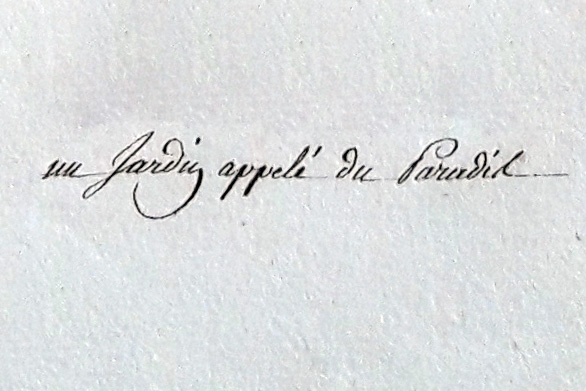

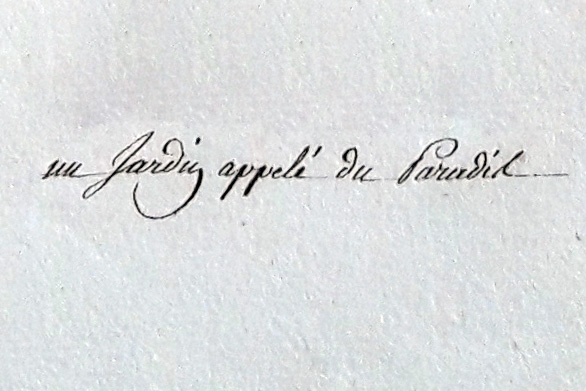

Further research into the archives of the Cantal district helped me establish that the origin of the name dates back to the reign of the kings of France, before the 1789 Revolution. The 1790’s ‘Inventaire des Biens Nationaux’, the list of properties seized by the revolutionaries, mentions that this ‘jardin appelé du Paradis’ (garden called Paradise), which measured ‘huit cent soixante dix-huit toises’, around 3,300 square meters, initially belonged to the ‘Chapelainie de Paradis’, the chapelry of Paradise, after which it was named.

This large garden must have been considered as a valuable property as its buyer paid three times the original estimate to acquire it when auctioned.

As mentioned earlier, the garden was then divided. The contract signed by my family when they purchased their plot seventy years later describes it as a ‘jardin dit paradis’, a garden called paradise. Our property had inherited the name of the big garden.

As we will see in the coming chapter, the Jardin du Paradis had been designed to produce food. My family maintained this purpose, even if the generation before me stopped cultivating vegetables and looking after the fruit trees, including those they planted in the late 60s. There are no more fruit trees in the garden today. Having said that, the architecture of the garden remained the same. It was just a question of recreating the vegetable garden and planting new trees. I started to do it in 2020 during the first Covid lockdown in France.

I had also started to plant new fruit bushes:

As a specialist of heritage fruit and vegetable garden conservation, I obviously had plans for planting new fruit trees, and for reviewing the general layout of the kitchen garden. I hoped we would someday see espaliered pear trees against the big fruit wall which enclosed the Jardin du Paradis to the North. The first step would have consisted in renovating the stone wall, keeping as many of its original architectural features as possible, including the remains of trellising nails and wires which demonstrated ancient horticultural practices.

A food-producing garden among many others in the area two hundred years ago

There were many kitchen gardens in and around Aurillac at the beginning of the 19th century. We can see them on the 1812 Martin map 1 where they were drawn.

Some of these gardens had probably already been there for a very long time. Kitchen gardens and their fruit were for instance mentioned in the resolution of a dispute between the powerful Aurillac Abbey and consular authorities called ‘deuxième Paix‘ (second Peace) in 1298 2. I am not sure how many of these ancient gardens still exist in the city of Aurillac today. I don’t know either when mine was built. But surely my Jardin du Paradis was old enough and its architectural features preserved enough for it to be considered as a piece of heritage worth protecting, especially as I, the owner of the place, wanted to conserve it.

Many of the gardens were walled, as this painting from the beginning of the 19th century shows:

The walls of fruit and vegetable gardens like mine had distinctive features. They were built on the sunny side of the hill, called adret in mountain agriculture jargon 5. To create the Jardin du Paradis, a terrace had been carved and a three metres high wall built against the carved hill, facing South. The wall regulated the ecosystem of the garden to maximise yield, in particular the production of grapes and fruit from espaliered trees. Carving the hill had also enabled the garden designers to reach the springs used to water the garden. There is still a well in my garden, and we could see until 2022 the remains of an arch at the bottom of the wall which suggested a catchment area.

Jacques Boyceau de la Baraudière, King Louis XIII gardener, described in 1638 the arboricultural practices of his time, in particular sun-facing walls and the cultivation of espaliered fruit trees against them, in his ‘Traité de jardinage selon les raison de la nature et de l’art‘ (treatise on the art of gardening with nature):

‘On en dresse (espaliered trees), parce qu’au printemps arrivent souvent des matinées fraîches et des gelées blanches, causées soit par la fraîcheur de la terre, soit par le vent du nort, qui gastent les fleurs plus hâtives et délicates… et nous ostent le consentement de leurs fruicts. Afin de prévenir de ces inconvénients qui sont assez ordinaires, on s’est avisé de chercher des abris contre des murailles qui, par leur hauteur et leur épaisseur, garantissent du mauvais vent, et, recevans les rayons du soleil, augmentent la force de la chaleur. Et les arbres plantés contre telles murailles, treillissez et agencez convenablement sur des perches y attachées, c’est ce que l’on nomme espaliers.’ (Boyceau de la Baraudière in Quellier, F., Des fruits et des hommes, 2006, page 135) 6.

My translation : ‘We train espaliered trees, because of frequent cool and frosty spring mornings, caused either by cool soil, or North wind, which destroy the early and delicate blossoms… and prevent us from benefiting from their fruit. In order to prevent these rather common nuisances from happening, we looked for shelters against walls which, thanks to their height and thickness, protect from bad winds, and, receiving sun rays, augment heat strength. And the trees planted against these walls, properly trellised and trained, are called espaliers.

I remember the espaliered pear trees which grew during my childhood along the wall of my Jardin du Paradis. Such arboricultural practices must have been applied for centuries in this and the surrounding gardens, in particular those from local convents and monasteries. Aurillac was famous at the end of the first Millenium as the birthplace and childhood home of the supreme pontiff of the year 1,000, Pope Gerbert; it remained an international landmark for centuries because of its religious institutions, in particular its abbey. ‘Gerbert of Aurillac was one of the most famous teachers/scholars of the late tenth century’ 7. I have no doubt that Aurillac benefited from the most advanced knowledge of agricultural practices that circulated across Europe in the Middle Ages, in particular the design and maintenance of fruit and vegetable gardens. The Jardin du Paradis was a live connection, direct or indirect, with this past.

2022

Unfortunately, the most distinctive element of the “Jardin du Paradis”, its ancient fruit wall, was destroyed in 2022. Its stones, the remains of old espaliering and the life it sheltered have been buried behind twenty centimetres of reinforced concrete.

Out of ignorance. Out of a lack of consideration. Out of a disrespect which culminated in private property violation. Out of a lack of competence too. Another solution than pouring concrete could have been designed and applied to renovate this wall. Discussing this as mutually respectful neighbours, we would have found a way for me to preserve, as I wished, a wall I considered as a beautiful piece of architecture made of local stone and a contributor to the ecosystem of my kitchen garden. It had been designed centuries ago to optimize food production. It was a piece of architectural heritage evidencing ancient practices of urban agriculture in Aurillac. The Jardin du Paradis was a place where the art of the espalier – the art of forming and pruning fruit trees for fructification, had probably been practiced for many centuries against that wall. An art included in the French intangible cultural heritage in August 2023 5.

This recognition of the importance of arboriculture practices by the French department of Culture unfortunately arrived too late for me. I couldn’t use it as an argument to safeguard my Jardin du Paradis. On 27 October 2022, they started to pour concrete.

___________

References (in French, except Ref N°7. Accessed 31 October 2023)

- http://bibliotheque-numerique.aurillac.fr/idviewer/2163/1

- https://www.cantalpassion.com/categories/376-avant-1900/3638-dr-aurillac?showall=1

- http://notesdemusees.blogspot.com/2020/10/aurillac.html

- https://www.decouvertes-occitanes.fr/fr/patrimoine-occitan/1185-le-cantal-vu-par-les-artistes-au-19-e-siecle-pascale-moulier-9782918098683.html

- https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adret

- Quellier, F. (2006), Des fruits et des hommes – L’arboriculture fruitière en Île-de-France (vers 1600-vers 1800), Presses Universitaires de Rennes

- The Students of Gerbert of Aurillac’s Cathedral School at Reims: An Intellectual Genealogy Courtney DeMayo, Heidelberg University

- https://www.culture.gouv.fr/Thematiques/Patrimoine-culturel-immateriel/Le-Patrimoine-culturel-immateriel/L-inventaire-national-du-Patrimoine-culturel-immateriel